Reading on: The universe according to Ptolemy

described by Anatole France, The Garden of Epicurus, 1920 [excerpt– 900 words]— the medieval worldview

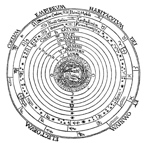

We find it hard to picture to ourselves the state of mind of a man of older days who firmly believed that the Earth was the center of the Universe, and that all the heavenly bodies revolved round it. He could feel beneath his feet the writhings of the damned amid the flames; very likely he had seen with his own eyes and smelt with his own nostrils the sulphurous fumes of Hell escaping from some fissure in the rocks.

Looking upwards, he beheld the twelve spheres,—first that of the elements, comprising air and fire, then the sphere of the Moon, of Mercury, of Venus, which Dante visited on Good Friday of the year 1300, then those of the Sun, of Mars, of Jupiter, and of Saturn, then the incorruptible firmament, wherein the stars hung fixed like so many lamps.

Imagination carried his gaze further still, and his mind’s eye discerned in a remoter distance the Ninth Heaven, whither the Saints were translated to glory, the primum mobile or crystalline, and finally the Empyrean, abode of the Blessed, to which, after death, two angels robed in white (as he steadfastly hoped) would bear his soul, as it were a little child, washed by baptism and perfumed with the oil of the last sacraments.

In those times God had no other children but mankind, and all His creation was administered after a fashion at once puerile and poetical, like the routine of a vast cathedral. Thus conceived, the Universe was so simple that it was fully and adequately represented, with its true shape and proper motion, in sundry great clocks compacted and painted by the craftsmen of the Middle Ages.

We are done now with the twelve spheres and the planets under which men were born happy or unhappy, jovial or saturnine. The solid vault of the firmament is cleft asunder. Our eyes and thoughts plunge into the infinite abysses of the heavens. Beyond the planets, we discover, instead of the Empyrean of the elect and the angels, a hundred millions of suns rolling through space, escorted each by its own procession of dim satellites, invisible to us. Amidst this infinitude of systems our Sun is but a bubble of gas and the Earth a drop of mud.

The imagination is vexed and startled when the astronomers tell us that the luminous ray which reaches us from the polestar has been half a century on the road; and yet that noble star is our next neighbor, and with Sirius and Arcturus, one of the least remote of the suns that are sisters of our own. There are stars we still see in the field of our telescopes which ceased to shine, it may be, three thousand years ago.

Worlds die,—for are they not born? Birth and death are unceasingly at work. Creation is never complete and perfect; it goes on for ever under incessant changes and modifications. The stars go out, but we cannot say if these daughters of light, when they die down into darkness, do not enter on a new and fecund existence as planets,—if the planets themselves do not melt away and become stars again. All we know is this; there is no more repose in the spaces of the sky than on earth, and the same law of strife and struggle governs the infinitude of the cosmic universe.

There are stars that have gone out under our eyes, while others are even now flickering like the dying flame of a taper. The heavens, which men deemed incorruptible, know of no eternity but the eternal flux of things.

That organic life is diffused through all parts of the Universe can hardly be doubted,—unless indeed organic life is a mere accident, an unhappy chance, a deplorable something that has inexplicably arisen in the particular drop of mud inhabited by ourselves.

But it is more natural to suppose that life has developed in the planets of our solar system, the Earth’s sisters and like her, daughters of the Sun, and that it arose there under conditions analogous in the main to those in which it manifests itself with us,—under animal and vegetable forms. A meteoric stone has actually reached us from the heavens containing carbon. To convince us in more gracious fashion, the Angels that brought St. Dorothy garlands of flowers from Paradise would have to come again with their celestial blossoms. Mars to all appearance is habitable for living things of kinds comparable to our terrestrial animals and plants. It seems likely that, being habitable, it is inhabited. Rest assured, there too species is devouring species, and individual individual, at this present moment.

The uniformity of composition of the stars is now proved by spectrum analysis. Hence we are bound to suppose that the same causes that have produced life from the nebulous nucleus we call the Earth engender it in all the others. When we say life, we mean the activity of organized matter under the conditions in which we see it manifested in our own world. But it is equally possible that life may be developed in a totally different environment, at extremely high or extremely low temperatures, and under forms unthinkable by us. It may even be developed under an ethereal form, close beside us, in our atmosphere and it is possible that in this way we are surrounded by angels,—beings we shall never know, because to know them implies a point of common contact, a mutual relation, such as there can never be between them and us.

Again,

it is possible that these millions of suns, along with thousands

of millions more we cannot see, make up altogether but a globule

of blood or lymph in the veins of an animal, of a minute insect,

hatched in a world of whose vastness we can frame no conception,

but which nevertheless would itself, in proportion to some other

world, be no more than a speck of dust.

Nor is there anything absurd in supposing that centuries of thought

and intelligence may live and die before us in the space of a minute

of time, in the confines of an atom of matter. In themselves things

are neither great nor small, and when we say the Universe is vast

we speak purely from a human standpoint. If it were suddenly reduced

to the dimensions a hazelnut, all things keeping their relative

proportions, we should know nothing of the change. The polestar,

included together with ourselves in the nut, would still take fifty

years to transmit its light to us as before.

And the Earth, though grown smaller than an atom, would be watered with tears and blood just as copiously as it is today. The wonder is, not that the field of the stars is so vast, but that man has measured it.